The Archive and the Chorus: Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

By Elisabeth Plumlee-Watson

What do we want from each other

after we have told our stories

do we want

to be healed do we want

mossy quiet stealing over our scars

From There Are No Honest Poems About Dead Women by Audre Lorde

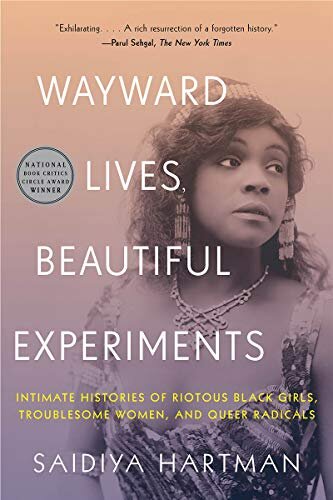

"Usually, to bring women characters to the fore in the writing of history (factual or fictional) you have to force the issue a bit," says Hilary Mantel, one of the most celebrated historical fiction writers of her generation. "You have to position them centrally, when they weren’t really central, to pretend they were more important than they were or that we know more about them than we do." Questions of “forcing the issue,” of “who matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of the historical actor,” are central to Saidiya Hartman’s recent book: Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (W.W. Norton, 2019). Hartman has devoted her scholarly career to researching and writing the lives of Black women living in the aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade, and Wayward Lives focuses on Black women and gender-nonconforming people living in Northern US cities between the years 1880-1940. All of them were poor and young, all were trying to achieve personal freedom of movement, relationship, and choice--not only in what Hilary Mantel calls a “masculine context,” but a context of genocidal mysegenoir and homophobia.

The obscurity that any historian or biographer is up against--that naturally imposed by death and time--was aggressively imposed on Hartman’s subjects while they were still alive. They were poor Black women and queer people who claimed sexual and relational agency: if you know anything about the world, you know that the world strove--and strives--to obliterate them. Obliteration came from Jim Crow and Tammany Hall law enforcement, yes; but also from enlightened settlement house social workers and doctors, and the virtuous exceptionalism exhorted by men like Booker T. Washington and Paul Louis Dunbar.

They were poor Black women and queer people who claimed sexual and relational agency

It isn’t that these people ignored poor Black women and queer people; to the contrary, they produced prodigious documentation on them. But these many documents and artifacts: “journals of rent collectors; surveys and monographs of sociologists; trial transcripts; slum photographs; reports of vice investigators, social workers, and parole officers; interviews with psychiatrists and psychologists; and prison case files,” every single one of them, “represent [Hartman’s subjects] as a problem.” To the historian of “the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved,” the archive is filled with paradoxical evidence of erasure and is at least as much adversary as accomplice.

Hartman frequently contends with the dominance of white, cishet male voices in the archive. But her most interesting, revelatory work shows the way that people at other intersections of oppression were deeply invested in limiting the agency of sexually and relationally free Black women and queers. She wrestles with the vital importance of WEB Du Bois' sociological documentation in The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899), The Souls of Black Folk (1903), and many other works, to the search for the lived realities of poor Black people in early 20th century American--but also how much of his early work on Black women was done with The Master's Tools. "He translated the stories of the ward into statistics and graphs, muting the voices and aggregating the lives into a grand sociological pattern"--a collection of data that was weaponized by city governments and social charities against promiscuous and poor Black women. "Statistics and ratios were not bloodless and abstract," Hartman finds, "but antagonists in the tragic tale of Black womanhood." His objectification of Black femme and queer sexuality, Hartman contends, allowed Du Bois a documentary barrier between himself and the trauma of being Black in America. "Nothing in the statistical tables asserted me too or risked being mistaken for an autobiographical example, or required the sociologist to yield to the heartbreak of cold facts."

One of Wayward Lives’ most detailed life accounts is the story of Mamie Sharp, a young Black woman who "like[d] to go about as I please." Extensive details about Mamie’s home life in the year 1888 are preserved largely because Helen Parrish, a Philadelphia settlement landlady, and wealthy white lesbian, was obsessed with her. In the chapter called "A Chronicle of Need and Want," Hartman unfolds the story of what happened the summer that Parrish's partner, Hannah Fox, was away at a Settlement House conference in London and Helen took Mamie Sharp and James, the man Mamie called her husband, on as new tenants.

The need and want chronicled are, to an extent, Mamie's: she had a deep need to assert her freedom of sexual choice, domestic arrangements, and movement as a young woman in the city. But the need and want are also--and more dangerously--Helen's. Helen and Hannah, her partner, came to the slums to do good--driven both by their convictions about racial justice and poverty and also for their want of power in the larger masculine context, because of a desperate need to escape the inward and outward indictments of their gender and sexuality. "In the slum, they avoided the indictment: spinster, surplus woman, invert." Helen, Hannah, and so many other white women like them, before and since, redirected attacks on their own queer sexuality onto the bodies and lives of poor young Black women.

Hartman works the biographical miracle of always centering Mamie's experience while never letting the reader forget that the record we have of that experience comes through the lens of a wealthy white woman's obsession: Helen kept a minute diary of Mamie's comings and goings, Mamie's fights with her partner, and her own confrontations with Mamie (and many other residents). From Mamie's arrival to apply for a lease in the block of subsidized apartments owned by Helen and Hannah, to the street shooting that ends Helen's involvement in Mamie's life, Hartman holds readers in the tension between amazement at the details available of Mamie's "refusal to be governed" and fury that all we have of Mamie is mediated by this white woman who was consumed by the allure of policing a Black woman's sexuality.

Halfway through Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Hartman tells the story of Gladys Bentley. Bentley was a masculine-presenting intersex person assigned female at birth, who, at the height of his career, was one of the most celebrated personas in Cabaret Halem, "a brilliant performer…[whose] queer masculinity...trashed the gendered norms and family ideals central to the project of racial uplift--self-regulation, monogamy, fidelity, wedlock, and reproduction." (Hartman gives a detailed footnote indicating her belief that he/him pronouns best represent Bentley’s self-identification, which guides my using masculine pronouns here).

Bentley’s flourishing success in the 1920s made him the ultimate villain of the cishet white myth…

Bentley’s flourishing success in the 1920s made him the ultimate villain of the cishet white myth, and vengeful forces of state and societal constraints eventually closed in. By the 1930s, "state law would require female performers to apply for a license to wear male clothes in their acts." Bentley tried to take his hugely successful acts from Harlem to Broadway where they were repeatedly shut down for “lewdness.” He moved back up to Harlem until the queer and drag cabaret scene there withered also. Hartman imagines the ways an archetypal villain might be sent to his death in a noir film: "a car crash, a bullet to the head or heart, or the penitentiary." But for Bentley, nothing would do but that oldest queer punishment: "self-renunciation” --to mythologize away his very self.

It is here that the two historiographical forces that Hartman traces throughout Wayward Lives--the objectifying observer and the marginalized subjectivity--are joined in one person, one artifact. The person is Bentley; the artifact is a "tell all" multi-page, highly illustrated article that Ebony Magazine ran in 1952 under the headline “I Am a Woman Again.” In it, Bentley gives a detailed account of his life as a gender-nonconforming person, beginning with being “born different...my mother refused to touch me,” up to being prescribed female hormones in order to marry a man “and make a clean break with my old life.”

In many of the photos run alongside “I Am a Woman Again,” Bentley is depicted in a frowsy housecoat, locked into meaning with breathless, wordy captions, eager to clarify the full triumph of cishet domestic bliss. We follow Bentley into the most intimate moments, as if to convince the reader that even--especially--in private, Bentley’s transformation is complete: “Turning back cover of bed, Miss Bentley prepares to make homecoming husband comfortable”; “Taste-testing dinner she has prepared for her husband, J. T. Gipson, Miss Bentley enjoys domestic role she shunned for years.” These elaborately staged photos run hauntingly alongside Bentley’s own words: “Our number is legion and our heartbreak indescribable.”

Chorus might be the idea Saidiya Hartman invokes most frequently throughout Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. “Chorus” evokes the cabaret culture of early 20th century urban America--a place of transgressive identities and a poor young Black woman or queer person’s narrow possibility of escaping poverty, if not racialized identity. It also evokes ancient Grecian performance: groups of unnamed singers and dancers, acting as interlocutors between the moral universe of ideas and the failings of both the audience members and the heroes onstage. Hartman hones in on the ancient Greek etymology of chorus that “refers to dance within an enclosure. What better articulates the long history of struggle, the ceaseless practice of Black radicalism and refusal, the tumult and upheaval of open rebellion, than the acts of collaboration and improvisation that unfold within the space of enclosure?”

So often while reading Wayward Lives, I thought of Audre Lorde’s provocatively titled poem “There Are No Honest Poems About Dead Women.” Hard words for anyone engaged in trying to honor the dead through truthful telling of their stories. But also, like so much of what Lorde wrote, an invitation to rigorously considered interrelationship. “What do we want from each other / after we have told our stories,” asks Lorde. Without any punctuation, let alone a question mark, she tumbles on, “do we want / to be healed do we want / mossy quiet stealing over our scars”.

Lorde’s words about “honest poems” echo Hilary Mantel’s observations about centering the marginalized in written history as “forcing the issue.” But Lorde’s question isn’t the academic focus of “what truths did the ‘masculine context’ warp for dead women” but “what do we--both the quick and the dead--want from each other.” This is the same place, in many ways, that Hartman arrives at the end of Wayward Lives when she turns her attention to “the chorus”--a polyphonous entity not confined by the archive or the past: “The chorus is a vehicle for a different kind of story,” she writes. To truly engage with this story transforms the writer and reader themselves into a part of that endless line of revolutionary history:

“If you are able to bear the burden of what they have to bring, then there is a place for you inside the circle and what you have suffered is part of the inventory...To fall in step with the chorus is to do more than shake your ass and hum the melody, or to repeat the few lines of the bit part handed over like a gift from the historian, as if to say, See, the girl can speak, or to be grateful that the sociologist has taken a second look and recognizes the working out of “revolutionary ideals” in an ordinary black woman’s life.”

To dance within the enclosure of marginalized peoples’ histories is to know the dance is neverending. Any biographies/histories/poems we offer up as being purely “about dead women” (i.e. The Other) are never fully honest--not only because of what the Master Narrative of the archive warped or neglected, but because to fully engage with the past is always in part communal, looking to the past as we lean toward futures we want for ourselves and for those as yet unborn.

Elisabeth Plumlee-Watson graduated from Vassar College with a degree in Religion and has worked in book business for her entire career, including almost 10 years in publishing. She served as Managing Editor of A Gathering of the Tribes from 2011-2014, and now works full-time as a buyer and bookseller at Loganberry Books in her hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. Elisabeth lives with her wife in Cleveland Heights. Her short-form writing can most frequently be found on Instagram @eplumleewatson.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals

by Saidiya Hartman

$17.95