Whitney Biennial 2010

With a name like “2010” you don’t really know what to expect when heading to the 2010 Whitney biennial. Unfortunately, you don’t really know what to think about the exhibit after leaving either. Though the theme of “2010” is justified by the curators Francesco Bonami and Gary Carrion-Murayari in the exhibit’s introduction as purposefully having “no theme” but rather representing the tenor of a generation, the biennial came across as scattered, disjointed, and lacking cohesion.

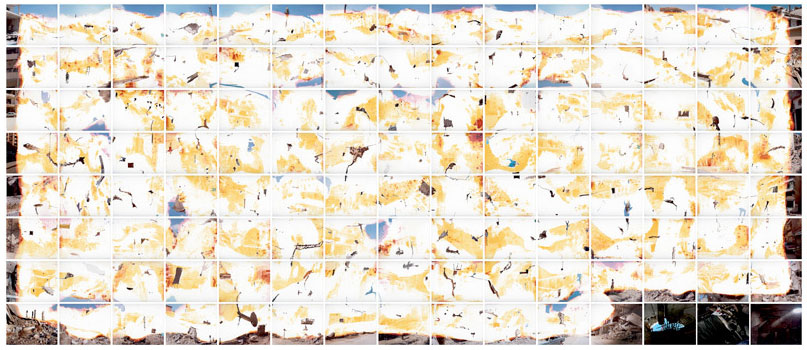

Walking into the Whitney Museum, the incoherent intentions of the exhibit came across almost immediately. While some of the artwork spoke to the political and social tensions of our time in direct and effective ways, such as Curtis Mann’s inventive After the Dust, Second View (Beirut) in which bleach is strategically used to conceal portions of photographs (found on Flickr) of the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah to create the illusion of an explosion, these powerful pieces were frequently followed by disappointing compositions whose attempts to articulate the frustrations of the time fell short.

Pieces such as Ania Soliman’s confusing NATURAL OBJECT RANT: The Pineapple, a collection of twenty-six photomontages (one for each letter of the alphabet) dedicated to the pineapple and it’s relationship to consumerism and colonialism seemed to reach towards an exploration of politics, yet the seemingly random subject (the pineapple) and the equally arbitrary decision to use the alphabet as a means of examination, left me distracted rather than focused.

Bonami and Carrion-Murayari peppered these outright politically explicit pieces with more abstract artwork that had a similar success rate. While some artists attempted to explore the process of production and perspective through the manipulation of a medium, others took a more direct approach. Scott Short’s engaging painting Untitled (white), reflects the illogical patterns of human perspective. Using the technique of photocopying photocopies, Short forcefully makes one question the permanence of interpretation. Conversely, R. H. Quaytman’s series of paintings and silkscreens entitled Distracting Distance, Chapter 16 which all focus on the architectural design of a window in the room of his exhibit, works with line and an established landscape to draw the viewer into the subject of perspective. Unfortunately, Quaytman’s predictable use of optical illusion fails to offer anything new to the discourse and is easily forgettable.

The disconnected nature of the biennial is not to say that the entire exhibit failed, and you will surely be both stunned and impressed by some of the more powerful, expressive and fascinating instillations executed by talented contemporary artists. “2010” simply falls flat in capturing the political and social moment in which we are living. Instead of acknowledging the apathy of (some) American youth growing up in a video-game culture, the stalemate of our partisan politics or the impact of two wars on all our lives, Bonami and Carrion-Murayari attempt to jumble anything and everything that can be interpreted as reflective of our time into four floors of art. Ultimately, it is too easy to say that the generation of 2010 lacks a theme; every age of creation has motif and time will tell that 2010 is no different. Unfortunately, the collection presented at the Whitney does not reflect the essence of “2010”.