The Richard Prince Fiasco

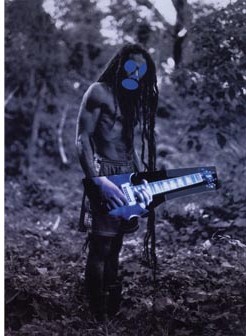

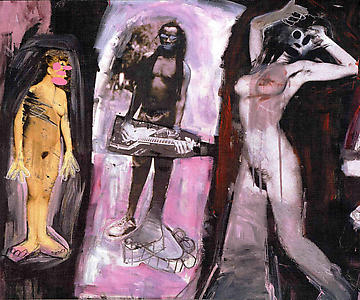

The irony of the case Patrick Cariou brought against Richard Prince is that it changes nothing. Prince remains as reclusive an artist as ever, following his own creative bent in his upstate New York studio, while the name Cariou is still only a curio: the man who was able to take Larry Gagosian to court, and actually win. For those unfamiliar with the details of the case, Richard Prince was accused by the French photographer Patrick Cariou of wrongfully pirating imagery derived from photographs taken by Cariou. Prince appropriated some twenty or so Cariou images for a series called “Canal Zone,” which exhibited at Gagosian New York. At around the same time, Cariou was denied the opportunity to exhibit some of these same images at a different New York gallery, as the gallerist who originally wanted to show his photography did not want to exhibit work similar to what was already on display at Gagosian. Disappointed, Cariou did what any civilized person would do in similar circumstances: he sued Prince and Gagosian for damages. And he won. The court actually ruled in favor of Cariou, and Prince’s and Gagosian’s lawyers are working to appeal the verdict. At the moment of writing this, the works Prince made out of the photographs taken by Patrick Carious have basically been impounded, but some of images are still available on the Internet. “Canal Zone” featured work that looks like this:

In light of this image, isn’t strange that we have to speak of “Canal Zone” in the past tense? Neither Cariou’s, nor Prince’s, the images here are the property of no one. Cariou’s certainly didn’t make them—nor, legally, did Prince. But the legal question that has been raised concerns the issue of “fair use.” Are the works Prince exhibited duly transformative of Cariou's? The Internet also provides us with images like this—

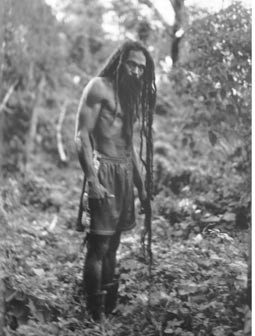

In light of this image, isn’t strange that we have to speak of “Canal Zone” in the past tense? Neither Cariou’s, nor Prince’s, the images here are the property of no one. Cariou’s certainly didn’t make them—nor, legally, did Prince. But the legal question that has been raised concerns the issue of “fair use.” Are the works Prince exhibited duly transformative of Cariou's? The Internet also provides us with images like this—

Such an image makes apparent the work that Prince started with. But can ANYONE really argue that Prince doesn’t create something toto genere different Cariou’s “original?” From tone to content, we’re viewing a completely different work.

Such an image makes apparent the work that Prince started with. But can ANYONE really argue that Prince doesn’t create something toto genere different Cariou’s “original?” From tone to content, we’re viewing a completely different work.

Does the case hinge on anything more than insecurity on Cariou’s part? If Cariou had been permitted a solo show, it’s possible that Prince’s appropriations might never have come under his radar. Perhaps the gallerist is to blame, then, for deciding against the exhibition of works similar to ones produced by Richard Prince? Arguably, a savvier gallerist could have turned the situation around to her own favor, as certain collectors would love to possess one of the “originals” from which a Richard Prince derives. But really there’s no one to blame; the case has in no way altered Richard Prince’s reputation, nor has it made Patrick Cariou famous. If anything, it has opened up a legal can of worms that more or less extends from Prince’s long-time creative practice, and even bolsters certain minimalist tendencies in his art. Some have spoken of copyright infringement—but even that is weak, and can easily pass notice. The fact that people pay any attention to case at all, though, signals that something is happening that they can’t quite articulate in terms of legality or creative sanction. And that’s just the issue: underlying the noise that even Prince himself is trying to move away from is the fact that creativity and privitization are butting heads in a painfully undialecitcal fashion.

Prince isn’t setting himself up as the spokesperson of anything; rather, he’s a player in a game that so-called liberal democracy has been playing for some time. Let’s consider the facts of the case, the origins of the complaint. Prince’s importance as an artist rests on how he makes works that are stylistically pure, valuing method over aesthetic results. He’s known to disassociate himself from works he has produced (and even sold), and has openly stated that he exhibits work he does not personally like. This kind of objectivity regarding his own methods and practice makes him suspect in a political climate that values ownership above all other things. And when Prince spoke in court about “Canal Zone,” stating how he constructed the series, and what he intended to result from it, he openly stated that he sought neither to delight, nor instruct, which made him culpable in that the court could not readily identify where Prince’s creative responsibility lay. If Prince had claimed that his appropriation of Carious’ photography was for didactic purposes, “fair use,” would have worked in his favor as a defense. But Prince was not trying to teach through Carious’ photography, so much as he was trying to continue tendencies he already saw implied by such work (which is different than anything contained in individuality of each Cariou’s “originals”).

When put on stand as a defendant, Prince was honest about what he trying to do: to make good paintings. A valid enough response, which should never have entered the context of a court of law. But as the work of Prince comes under fire, his techniques have also become visible to a wider audience. And it would seem that Prince and Gagosian lost their case, not because Prince did not in fact rework exiting materials begun by Cariou, but because the judge who presided over the case thought Prince’s work was bad. For the record, then, let it be known that the methods of appropriation practiced by Richard Prince are strategic inversions of the style made famous by Andy Warhol, especially in the latter’s Double Elvis (1963) and Lemon Marilyn (1962). But Prince’s appropriations are not motivated by Warhol’s working-class yearning to possess what one doesn’t have. Prince appropriates as the result of an acculturated immersion to an environment where everything is reduced to generic types. Hitherto visible mainly to connoisseurs of art, Prince’s appropriations perceptively toy with the established conventions of what art can be, what it’s designed to appear as and what it’s expected to accomplish. The fact that his art has now entered the courts gives his work political ramifications which even Prince does not suspect.

When put on stand as a defendant, Prince was honest about what he trying to do: to make good paintings. A valid enough response, which should never have entered the context of a court of law. But as the work of Prince comes under fire, his techniques have also become visible to a wider audience. And it would seem that Prince and Gagosian lost their case, not because Prince did not in fact rework exiting materials begun by Cariou, but because the judge who presided over the case thought Prince’s work was bad. For the record, then, let it be known that the methods of appropriation practiced by Richard Prince are strategic inversions of the style made famous by Andy Warhol, especially in the latter’s Double Elvis (1963) and Lemon Marilyn (1962). But Prince’s appropriations are not motivated by Warhol’s working-class yearning to possess what one doesn’t have. Prince appropriates as the result of an acculturated immersion to an environment where everything is reduced to generic types. Hitherto visible mainly to connoisseurs of art, Prince’s appropriations perceptively toy with the established conventions of what art can be, what it’s designed to appear as and what it’s expected to accomplish. The fact that his art has now entered the courts gives his work political ramifications which even Prince does not suspect.

-Jeffrey Grunthaner