Divine Comedy reviewed in the Villager

BY LAEL HINES | “I got stabbed. It was no big deal, small deal, small deal, small deal. It was stupid. “I was working at this bookstore on St. Mark’s Place near Second Ave. on the south side of the street,” Ron Kolm recalled. “I was up behind the register and we used to get robbed all the time. The counter actually had an opening on both sides, so we could run away.

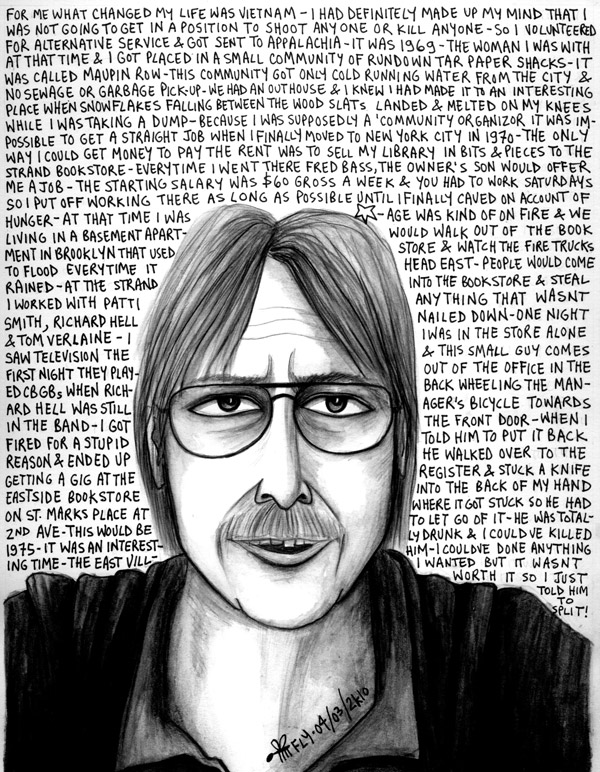

“Anyway, I was there alone one night and this guy came in, went into the manager’s office and tried leaving with the manager’s bike. You know, I said, ‘Yo dude, you can’t do that. Put it back.’ He was drunk out of his mind; it was like this cloud of alcohol surrounding him.

“And he came up to me at the counter and pulled out a knife and whacked it in my hand,” Kolm said. “The knife is stuck there and he couldn’t pull it out. It was actually kind of funny. I said — because this is the asshole I am — ‘You’re really small and you’re really drunk and I could probably kill you if I wanted to, but it would be pointless. Your life is a pointless life, so I’m just going to ask you to get the fuck out.’ ”

“It’s been a good trip,” said Kolm, as he reflected on his life, living in New York and working in bookstores since the late ’60s.

PEOPs portrait project by Fly - www.peops.org Ron Kolm – 04/03/2k10 – Lower East Side NYC Local Unbearable Writer – www.unbearables.com

Kolm’s experiences stimulate and inform his writing — poetry and prose that paint stories and images that are both relatable and barely believable.

With his characteristic self-deprecating tone, Kolm explained, “You have to understand what an asshole I am. A part of me is this guy going through life and another part of me is this guy watching it or commenting, the writer the observer, if you will.

“It was a gift that I saw the thing happened or that I saw the size and shape of it,” he said. “I don’t just try to write poems about anything. I try to look for things that have a shape and cut it out of that shape, the same way a sculptor sees something in a block of marble. You’re trying to free something that you see in there. That’s a cliché — but, most of my poems are based on real events. ”

With New York as the usual backdrop, the turbulence in Kolm’s life has sparked literature that similarly stimulates rebellious and revolutionary emotions among readers.

“I’ve had a little bit of luck with my tiny, silly-ass career,” said Kolm with concise irony. His “silly-ass career” has effectively produced his most recent book of poetry, “The Divine Comedy” (Fly by Night Press). With poems with titles like “Butt Sex” and “Hand Jobs,” Kolm as an artist is clearly unbound by societal perceptions or restrictions.

His revolutionary spirit has been resonant since the late ’60s.

“I did become antiwar ” he exclaimed, “but I didn’t go to Vietnam. I worked in Appalachia as a community organizer, which actually did shape my life. I worked with really poor people and I never quite made it back to the mainstream in America. Thank God, in a way. I try to use some of that stuff in my writing. A lot of shit happened.”

Kolm’s radical mentality effectively instigated the formation of The Unbearables. The Unbearables are a group of revolutionary writers who have rocked the New York City literature scene with their humor-filled, radical actions since 1984.

“We would picket the New Yorker, protesting their shitty poetry,” Kolm recalled. “We would do erotic readings on the Brooklyn Bridge every September 13. We would read to businesspeople as they went from Manhattan to Brooklyn. It was a fun thing to do; it was a little bit like being back in the ’60s.”

Most of Kolm’s actions align with a desire to be radical while fighting against the generic mainstream. He described this as one of the main inspirations of his writing.

“This culture is based on things wearing out, on selling things,” he explained. “I like to feel if you do a piece of art that doesn’t become instantly obsolete — it’s going to stick around for a while — you’ve actually done a small blow against the empire, and I genuinely believe that.”

For Kolm, radical literature shaped his existence.

“I was a fucking fascist when I was growing up in Pennsylvania,” he said. “It was art and literature that got me out of that. Reading ‘Catch-22’ changed me.”

By creating wonderfully rich and rebellious works like “The Divine Comedy,” Ron Kolm perhaps aims similarly to inspire readers, lifting them out of the often-superficial elements of American mainstream society.

“American culture is like dead in the water,” he declared. “It’s as close to the ’50s as I can remember. People are scared of being different and nobody really knows what to do.”

With his humanistic worldview, Kolm certainly harbors a discontent with the current generation. Expressing his annoyance with the world today, he said, “When I moved to New York in ’69-70 it was ridiculously cheap. You could get apartments for $100 a month. What’s happened is New York has gotten incredibly expensive — it’s just gone up and up and up.

“It’s almost impossible to live here now unless you move out to the ghettos,” he continued. “Bushwick, Bed-Stuy. I mean Bed-Stuy, for God sake! In the old days you wouldn’t even go close to that place because you’d be afraid you would just die.”

Fitting for a modern-day humanist, Kolm has a love of antiquity.

“Basically, my degrees are in history,” he noted. “What I enjoy are reading books on ancient Roman history.”

In fact, he described his belief, as he put it, that, “New York is Rome — ancient Rome. I think of 9/11 being New York’s 410 [the year of the sack of Rome]. I think that event influenced the city in more ways than we know it.”

Kolm’s connection to antiquity is fully represented in his “The Divine Comedy.” His poem of the same name fully parallels the work by Renaissance Humanist Dante. Kolm explained, “There are three movements. There is an attempt to move upward toward heaven the entire way through. The three movements vaguely mirror the three movements of ‘The Divine Comedy,’ I sort of fell into it.”

Near the interview’s conclusion, Kolm once again expressed his ironic, self-deprecating take on things.

“I’m so glad my mind still works,” he said, though adding, “It doesn’t really work anymore. I used to really like my mind. It wasn’t a bad mind. I managed to be very lucky.

“There’s the writer part of me that I like,” he said. “But there is another part of me which is just this old guy deteriorating. I see old guys going around in their little motorized chairs and I think, Oh fuck, that’s going to be me someday.”