Seven Postwar American Painters by Carl Watson

See It Loud: Seven Postwar American Painters@National Academy Museum Sept. 26 2013 to Jan. 26 2014

“See It Loud,” the aptly named current show of painting at the National Gallery Museum has been assembled by by Senior Curator for the National Academy, Bruce Weber Ph.D, (who is also the well known poet and poetry impressario). The exhibition showcases seven postwar (male) painters, and is roughly divided between figuration and landscape. All these painters have at one time or another been members of the National Academy, and the all works have been gathered from the collection of the Center for Figurative Painting on 35th Street which is devoted to postwar figurative artists. That said, this exhibition is based around the conflict between abstraction and representation, as faced by this generation of artists who came of age in the 40s and 50s (though many works date from later decades), and who faced the legacy of the abstract expressionists while at the same time seeing and seeking a set of broader possibilities. As the museum director, Carmine Branagan, puts it: “This group of painters all working during the post-war years and mostly in New York City emerged in the wake of Abstract Expressionism and forged an original and dynamic synthesis between representational imagery and the principles of abstraction.” The divide between representation and abstraction was, at the time, more crucial in the art world than one might assume. Dr. Weber begins his catalog introduction by stating: “Many of the artists featured in this exhibition began their careers at a time when abstraction and representation were not only polarized in the American art world, but seemed irreconcilable. There was very nearly a moral dimension to the opposition between the two aesthetics,” and painters were expected to choose an allegiance. The painters in this show can be said to have crossed or disregarded that so-important aesthetic line. However, it can also be ambiguous what crossing such a line means in terms of the artist’s and the viewer’s experience. Do the works engender a sense of conflict or of fashionable comfort? Do we detect a rebellious disregard for the current dogmas of the art world, or rather a lack of commitment, an aesthetic of indecision? Are we looking at exploration or a kind of cover-all-bases complicity? Is synthesis or abandonment the primary gestalt here? Knowing the context of the show, my inclination, as an outsider, i.e., a viewer with no art historical background, was to discern, as best I could, where and how that conflict manifest itself. Thus what follows are capsule impressions without authority whatsoever to back them up.

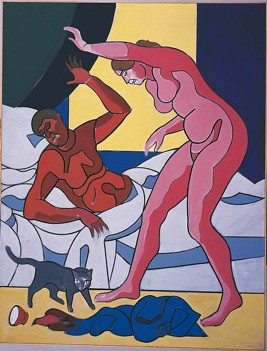

Leland Bell (1922-1991)

Bell’s large canvases depict, at least in this exhibition, domestic scenes. The figures are boldly outlined and the colors, strong and aggressive. His “representational” pretense can be seen as a scrim of sorts over a more abstract reality that seems to pressure the surface the scene from underneath or behind, as if chaos sought to press through and assert its fragmentational influence over the structural order of domesticity. The bold outlines thus serve, or defend, order against that underlying chaos. In fact, one can see Bell’s reoresetational forms re-purposed as a kind of armor plate in an anxious reality. And the figures in Bell’s painting do seem to be acting out, on a quotidian level, some meta-physical strife as virtually every scene seems to revolve around some sort of drama, perhaps ritualistic, which the viewer can only surmise, or as one critic put it: “daily existence at the level of myth.” This tension of violence under domesticity is nothing new but is rendered by Bell with gestures that remind me Blake’s tortured and yearning figures. One curious note: often the scene is punctuated by the presence of an animal—a dog, cat or bird—that seems to act as the catalyst for a drama that likely has nothing to do with it; the animal becomes a contrasting irritant to the emotional human world precipitating the scene.

Leland Bell, Morning II, 1978-1981. Acrylic on Canvas. 89 1/4 X 68 ½

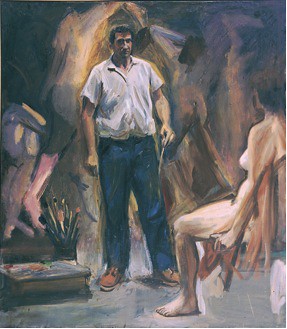

Paul Georges (1923-2002) Georges, like Bell, is a figurative painter, but his subject matter is primarily the artist himself, the man “as painter” facing the representational question: how does one render this world in a meaningful way and why bother. For Georges it seems that the question is the meaning. A number of the paintings here are self-portraits: we see Georges standing in his studio before his easel or his model, in an act of self-inquisition or doubt. Even when the focus is not himself, Georges’s question is present: in “Scene at the Cedar Tavern” artists being artists is the subject. But of course in the corner we see Georges staring out at the viewer drawing attebntion to his personal dilemma. (A group of the artists in this exhibition hung around at the Cedar Tavern which is at least part of the reason why abstraction weighed heavily on their aesthetic.) One might say that abstraction enters these paintings here like a miasma, an aura of the past that colors the present, a darkness borrowed from Dutch grotesques or moldering cubist works that must be reaconed with. Even when Georges is focussed only on his model, his nude subjects staring back, with a certain look as if to ask “So Paul what are you going to do with this?” a question that can be read both as a taunt and as a demand for identity on the artist’s part. Georges is also drawn to allegorical subjects and the title of the painting, “The Mugging of the Muse,” with a simple change of definition, could cover his entire oeuvre as represented here, i.e the artist mugging for his own eye, the artist as his own muse.

Paul Georges, Artist in Studio, 1963. Oil on Linen. 80 1/4 x 70 ¼

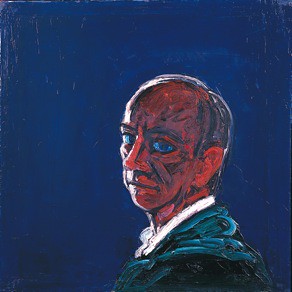

Peter Heineman (1931-2010) The obsession with self-representation brings us to the work of Peter Heineman, who at least in this show is obsessed with his own head. In fact, most of the paintings are titled “Head.” The viewer walks into a room full of portraits of the artist’s blue-eyed head done with wide thick brush work, lines verging on abstractions, and most noticeably, bold colors verging on florescent. Many of the portraits have a distinct otherworldly glow, especially Heineman’s eyes, which seem back-lit light a computer screen. This is meant, I suppose, to indicate the fire of identity, but it can also be read as the utterly indifferent mechanics of the computational mind churning out the character each of us believe we are. In fact, Heineman does see these portraits as a dialogue with himself over time, a chronology or map of characters he has played in his life: “a parade of the human condition gleaned from facets I found in myself: murderer, pimp, panderer, liar, charlatan, dufus, deviate, failure, prideful pompous ass, slothful braggart, false prophet, whimp ….” The self for Heineman seems to be an ever-changing entity, caught up in a feedback loop with itself and rolling backwards and forwards in time.

Peter Heineman Head, 1987. Oil on Canvas/linen. 28 x 28

Peter Heineman Head, 1987. Oil on Canvas/linen. 28 x 28

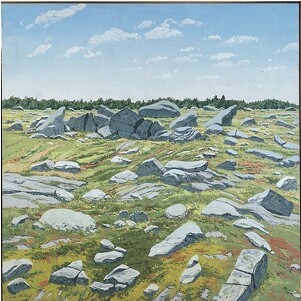

Neil Welliver (1929-2005) With Welliver we are solidly in the realm of the landscape: mountain vistas, barren fields, rocky hillsides, woodland streams viewed through tangles of foliage. There is an elevating, uncongested quality to these works; they are full of skylight, natural color, and fresh cold clean air. Such imagery would seem the antithesis of the molecular and subatomic warrens of abstraction. But it is in “the landscape” that we might look for commentary on the relationship between representation and abstraction. After all, it has been claimed that abstraction is, in fact, an extension of landscape painting. Cross your eyes as you look at the world and you can make it happen, or use your perspective as a framing device and simply move in so close, or out so far, that your personal and cultural definitions become irrelevant. Every line, every form, will eventuallyt dissolve under the pressure of scrutiny. However, it is also possible to claim that such paintings as these question the very idea of abstraction, i.e does abstraction exist as a genuinely separate truth. Can forms and relationships be created that cannot also be found in nature? In the infinite complexity of our physical world that prospect is doubtful. Nature already provides all abstraction, especially if you strip away the human context. Abstraction is merely the imaginations grasping at the yet unseen, or in the case of Welliver, the making of the seen into the unseen, which is the artist’s job.

Neil Welliver, Midday Barren, 1983. Oil on canvas. 96 x 96

Paul Resika (b. 1928) In the paintings of Paul Resika we see landscape that is in fact constantly crossing over into the “abstract.” Resika, in this show, is a painter of boats, beaches, piers, water side scenes. Sails and moons are some of his main subjects rendered with a Klee-like playfulness coupled with a Gauganesque exoticism. The viewer immediately understands that these shapes, and the vistas they inhabit, are only excuses for the painterly play. Thus with Eresika, the painter , a man who wished to “escape the tyrrany of things,” we get only a hint of the “represented,” object, left to float or dangle against a background of bright color that alternates per canvas between hot reds and oranges or cool blues and greens. As Weber writes: “Boat and building-like forms morph into hot and radiantly colored geometric shapes, including rectangles, triangles, squares and circles which are flushed against a background field of bold monochromatic color.” Resika’s world is ungrounded, water born or air born, and the “things” in it are suspended in a frozen moment of perpetual motion. Where the curvature of organic forms such as branching tree limbs of a woman’s body appear, they are absorbed into the angular world, what one critic called: “the vastness of the plane of the sky against the elusive assertion of the sea,”

Paul Resika, Moon and Boat (Pendulum), 2003-2007. Oil on Canvas. 81 x 65"

Paul Resika, Moon and Boat (Pendulum), 2003-2007. Oil on Canvas. 81 x 65"

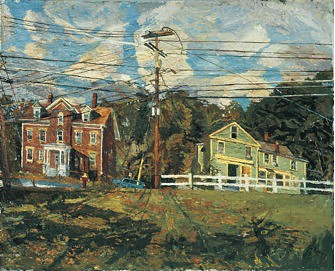

Stanley Lewis (b. 1941) Some of my favorite paintings in the show are the landscapes of Stanley Lewis. From a distance they seem to be typical representations of small town streets: houses, telephone lines, foliage. But even at a distance one detects a troubling, almost oppressive density and, something else—a disturbed surface that roils the scene. Getting close to the painting the viewer realizes that the painted surface is in fact a landscape unto itself, separate from what it “represents.” The thickly layered paint has hills and valleys that command the eye while contradicting what appears on the surface. Lewis is known for cutting away whole sections of the paintings in order to redo a square inch here or there. Eber describes it this way: “During the course of creating his painting he builds up the surface, cuts it pieces it together, scrapes away some details and even entire regions. Areas of thick impasto lie adjacent to sections splattered with light delicate strokes. Some of the surface is five or more layers thick and so densely covered with paint that portions buckle or swell, so that the surfaces of his canvases are full of concavities and convexities.” One critic speaks of a sense of “Cubist dislocation.” And it is true that normal perspective goes haywire and the scene that seemed so quotidian and comforting starts to suggest but a scrim, a trompe l’oeil on the surface of a turbulent reality. What we think we see or know becomes an illusion but not necessarily a frightening one. Indeed, there is a sensuous quality to the thick curving surface of paint that invites inspection as does the endless depth of the forest floor, a moss covered and time eaten stone, the roiling green of the deep sea, or the body of a lover.

Stanley Lewis, Two Houses in Leeds, 2004. Oil on Canvas. 17 x 21 3/16"

Stanley Lewis, Two Houses in Leeds, 2004. Oil on Canvas. 17 x 21 3/16"

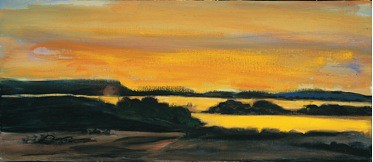

Albert Kresch (b. 1922) Another landscape painter, Albert Kresch, is my my second favorite in the show. Kresh paints landscapes that are low and flat and seem like geological slices or layered mood sandwiches made of accretions of light and time. Weber tells us that the paintings are “organized around the interplay of subtle plastic rythms and resonant bands of color,” Though the paintings are small they seem to stretch horizontally in all directions, suggesting space and time. Kresch paints the land in the light of transition – twilight, and he is a wizard with the unique color justapositons of these transitional times. Black forms highlighted by sunlit patches of grass or water. The skies often mirror the land and are subtly done with an eye to augmenting the transitional mood. Buildings such as they are exist as soft boxes, and human figures are seen as ghostly blurs. Some critics have called Kresch’s work “jazzily geometric,” or “off balance,” or “off kilter.” I don’t see such descriptions applying to his landscapes, however, rather there is a rolling eroticism to ghis landscapes – an erotics of the tempted eye, that is more romantic, impressionistic than aggressive or disorienting.

Albert Kresch, Landscape #4, 1993. Oil on Canvas. 11 1/2 x 26"

Albert Kresch, Landscape #4, 1993. Oil on Canvas. 11 1/2 x 26"

One of the interesting qualitiess of the show, as Bruce Weber has arranged it, is that though each artist seems to be represented by a particular period and style of their work, there are inclusions of from earlier or later periods to provide contrast. The show catalog has even more of this development.

All these artists pay their homage whether willingly or not to the earlier generation of modernists: impressionists, expressionists, cubists, futurists, abstract expressionists. Some of the flavors and moods I detected were those of Matisse, Cezzane, Gaugin, Klee, Picasso, Albers, Mondrian, Bonard, Arp, Munch, Roualt. But each of the painters have developed a distinct style of their own. Bruce Weber has done a great job with this show and the National Academy Museum is a great place to see it, an old-school museum with an atmosphere of integrity and quiet that contrasts positively to the circus chaos of its neighbors on museum row. “See It Loud” runs until Jan 26th. You’ll find something there to inspire.

reviewed by Carl Watson