Patricia Spears Jones reviews Dawoud Bey at the Mary Boone Gallery

DAWOUD BEY: THE BIRMINGHAM PROJECT Mary Boone Gallery, May 1—July 19, 2014 Dignity and Candor: Diptychs by Dawoud Bey By Patricia Spears Jones

2014 is an important year. Many anniversaries are being celebrated or acknowledged. But none more important for Americans than the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act and the year in which the Civil Rights Movement was in full defiant mode. Freedom summer, protests, murders, riots -- 1964 had it all. But what was happening had much to do with what had happened in

Birmingham, Alabama, a town where Black people’s lives were under constant threat and where a series of explosions gave the city the nasty nickname, “Bombingham”. On a Sunday in September, 1963, four Black girls were murdered at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church (Denise McNair was 11 years old, while Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins and Carole Robertson were 14. And hours later two black boys, Virgil Ware, 13 and Johnny Robinson, 16 were killed in separate racist attacks. In 1963, I was 12 and I so identified with those girls.

Dawoud Bey also identified with those youngsters, although he was growing up in New York City. His people, however came from the South and so clearly understood and conveyed the brutality of entrenched Whites and the courage and danger faced by Blacks. Those deaths haunted him. And so he found a way in The Birmingham Project to bring his immese artistry and skills to bear on a series of portraits that honor the memory of those girls and boys, and shows the capacity of African Americans to carry on, indeed to thrive, in the face of so much hatred. Diptychs by Bey were on view at the Mary Boone Gallery on Fifth Avenue early this summer.

Over the past two decades, Dawoud Bey, an award-winning, accomplished photographer and professor at Columbia College, Chicago, has chosen as his subjects, people are often portrayed by others in either banal or sensationalist ways such as adolescents, particularly Black teens. Bey’s perspective is as an African-American artist deeply committed to allowing for the full complexity and sophistication of Black people, including their dignity to be expressed in his work. His teens may be sullen, but they are not banal. His street people may be poor, but they are not stereotypes. He looks for a humanity that other Black artists, from Langston Hughes to Clifford Brown, have sought and found, and he brings a perspective that in the hands of a lesser photographer would be simplistic and didactic. He is not a lesser photographer. He is an artist working at the top of his game.

After several visits to Birmingham over six years, Bey developed a strong rapport with the local community including several prominent Blacks involved in civil rights archives; in local activism and culture. He contacted the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a reluctant shrine to hatred and hope. With an invitation from the Birmingham Art Museum, Bey developed a project in which he paired elder Black Birmingham residents who would be around the age of the murdered girls and boys with young people who were the age of the children who died. These black and white sitting portraits are elegiac and celebratory—a rare feat. The installation at Mary Boone is careful—in a way almost too careful, I think. But the calmly painted walls and understated lighting focuses the eye on the pictures. Viewers take in the whole of each portrait and then their sum in a sweep of large-scale framed photographs -- each diptych measures 40x64 inches. While not as large of some recent photographs I’ve seen, these works pack quite a visual wallop.

Indeed, while these pictures were up at Mary Boone Gallery, others were hanging on the fourth floor of the Whitney as part of the Biennial, along with Dawoud Bey’s portrait of President Obama.

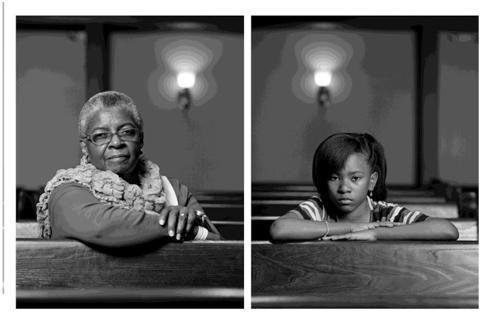

One can only imagine what it must have been like to have seen these photographs in Birmingham at the Museum. The photographs were taken at the museum and at the Bethel Baptist Church over several months. Two of these diptychs showcase the power and beauty of Bey’s endeavor. This photograph of Mary Parker and Caela Cowan illustrates the artist’s strategies—these are all sitting portraits. Gestures mimic, but may not be identical to each other. Neither subject smiles, but Ms. Parker hints at some mischief. Her young cohort is serious. They share a powerful legacy and yet Ms. Parker lived that history while Ms. Cowan has to deal with the legacy.

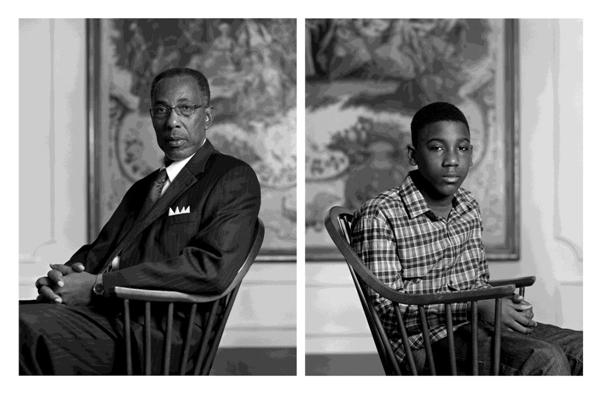

Another impressive pair is two males: Don Sledge and Moses Austin. They sit in identical chairs -- a paired profile. An old man looking back, possibly, a young man looking ahead? Both are full of their own strengths and vulnerabilities. Bey’s portraits are never quite so easy to read and why should they be? Birmingham is a place of great pride, great loss, fear and possibilities.

Another impressive pair is two males: Don Sledge and Moses Austin. They sit in identical chairs -- a paired profile. An old man looking back, possibly, a young man looking ahead? Both are full of their own strengths and vulnerabilities. Bey’s portraits are never quite so easy to read and why should they be? Birmingham is a place of great pride, great loss, fear and possibilities.

Bey’s response to this invitation was to give the citizens of Birmingham and enthusiasts of portrait photography powerful images that capture that mixture of pride and loss. The choice of elders and children reflects his ongoing exploration of generational evolution. The connection to the South and to Southerners who stood up against deep oppression and violence is palpable. Bey finds a way for his camera to extend a story that continues to unfold to this day. In an era when much is ironic and empty, his work thrives on an earnest regard for his subjects, superior technique, and a willingness to go wherever and work with whomever to reclaim the human fact that history often obliterates. He has honored those girls and boys. He has honored the Black citizens of Birmingham. And he has continued to join a sustained assault by many photographers of color against racist imagery. Dignity and candor are difficult to convey but in Bey’s camera eye--those qualities abide.

Dawoud Bey: The Birmingham Project is at Mary Boone Gallery, 545 Fifth Avenue, May 1-July 18. All photographs are copyright Dawoud Bey, 2012. Each photograph is 40x64 pigment print. For more information on the accompanying exhibition catalogue go to

http://www.birminghammuseumstore.org/info.html and for more information on Dawoud Bey’s work and career, go to www.dawoudbey.net

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Patricia Spears Jones is author of three collections, most recently Painkiller (Tia Chucha Press)) and four chapbooks including Living in the Love Economy (Overpass Books, 2014) and two plays commissioned and produced by Mabou Mines, the acclaimed experimental theater company. Her new collection: A Lucent Fire: New and Selected Poems is due out from White Pine Press, Fall 2015. Poems are anthologized in Angles of Ascent: A Norton Anthology of Contemporary African American Poetry (W.W.Norton); broken land: Poems of Brooklyn ((NYU Press) and Best American Poetry: 2000. (Scribners) and the bilingual anthology, Mujeres a los remos/Women rowing: An Anthology of Contemporary US Women Poets (El Collegio de Puebla, Mexico) and several additional ones. She is editor of and contributor to Think: Poems for Aretha Franklin’s Inauguration Day Hat http://bombsite.powweb.com/?p=2944 and Ordinary Women: An Anthology of Poetry by New York City Women and is a contributing editor to Bomb Magazine. She is the recipient of awards from The Foundation of Contemporary Art and The NY Community Trust (The Oscar Williams and Gene Derwood Award),the Goethe Institute and grants from the NEA and NYFA. She served as a Mentor for Emerge Surface Be, a new fellowship program at St. Mark’s Poetry Project and is a Senior Fellow at the Black Earth Institute, a progressive think tank. She is a lecturer at LaGuardia Community College.