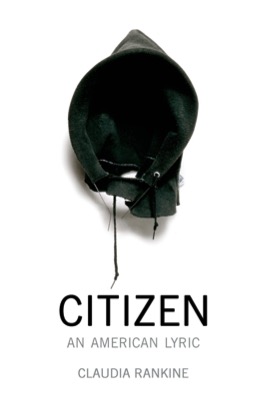

Against a Sharp White Background: Race and Decorum in Claudia Rankine's Citizen

Against a Sharp White Background: Race and Decorum in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen

By Rob Bryan 7/8/2015

Photo credit: David Hammons

Writing recently in The New York Times Magazine, the poet and professor Claudia Rankine addressed the possibility for constructive mourning in the wake of the Charleston massacre:

National mourning, as advocated by Black Lives Matter, is a mode of intervention and interruption that might itself be assimilated into the category of public annoyance. This is altogether possible; but also possible is the recognition that it’s a lack of feeling for another that is our problem. Grief, then, for these deceased others might align some of us, for the first time, with the living.

In the media, empathy for black life is closely tied to the spectacle of public tragedy. The deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Dylann Roof’s victims in Charleston all elicited genuine displays of sorrow from white liberals, but the news coverage of their lives tended to ensure that the Otherness of these “deceased others” remained intact. To bridge this gap and “align some of us…with the living” requires cultivating an empathy that encompasses the quotidian as well as the newsworthy.

What does the everyday experience of racism feel like? This is the central question Rankine tackles in Citizen, a book of poetry that also incorporates visual art and fragments of essayistic writing into a loosely assembled collage. Her setting is not the blighted inner-city ghetto or the prison, but the manicured lawns of white suburbia and the genteel interactions of the academy. When she explores the notion of memory, it is not the abstracted collective memory of slavery or Jim Crow or the civil rights movement, but the personal memory of an individual unable to escape her past:

Not everything remembered is useful but it all comes from the world to be stored in you. Who did what to whom on which day? Who said that? She said what? What did he just do? Did she really just say that? He said what? What did she do? Did I hear what I think I heard?

These questions replicate the thought process of someone constantly put on the defensive, questioning what she knows she heard and saw but would rather forget, caught off guard in a way that she’s used to, surprised at her own surprise. Every moment presents a choice between anger and composure, an uncomfortable honesty or a stifling silence. She may raise an objection, as she does to a man who uses a racial slur in a coffee shop, or she may purposely overlook the utterance for the sake of maintaining decorum, or for the sake of friendship, or for the sake of fighting the seemingly inescapable stereotype of the Angry Black Woman.

Rankine briefly mentions a photograph that a friend saw of her on the Internet. The friend wants to know why she looks so angry even though she and the photographer chose it because they agreed it looked the most relaxed. Once again, she is on the defensive, unsure how to respond: “Obviously this unsmiling image of you makes him uncomfortable, and he needs you to account for this.” She continues, “If you were smiling, what would that tell him about your composure in his imagination?” This anecdote, all related in nine lines of prose, says so much with so little; the projection of racial animosity on a neutral expression, the implicit obligation to put white people at ease, and the tenuous nature of friendship are all communicated in the simplest language. This simplicity, rather than obscuring emotional nuance, sharpens its contours so that the racial implications of her friend’s words are unmistakable. The subtext does not have to be excavated from elaborate metaphor – its ugliness is made clear by the words of Citizen’s nameless characters.

By putting her memories in present tense, Rankine restores their immediacy. Describing her arrival at an appointment with a therapist, she writes:

At the front door the bell is a small round disc that you press firmly. When the door finally opens, the woman standing there yells, at the top of her lungs, Get away from my house! What are you doing in my yard?

Moments like these form the backdrop of Citizen, the base from which Rankine can expand on the feelings of being an outsider in her own neighborhood, or even in the front yard of a therapist who, she wryly notes, “specializes in trauma counseling.” The incidents, she suggests, though less tragic than a police killing and less newsworthy than a riot, are still significant. A micro-aggression like those she describes might not be the straw that breaks the camel’s back, but it’s a straw nonetheless, and the accumulated weight of these straws is unbearable.

Quoting the artist Glen Ligon (whose art is reproduced in the book), Rankine writes, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” The notorious outbursts of Serena Williams and Zinedine Zidane are used to illustrate this motif. Rankine’s writing it at its most prosaic during her discussion of Serena Williams, and she makes it clear that she believes there was a racial component to the bad calls that led to Serena’s McEnroe-esque tirade against an umpire during the 2009 U.S. Open. Her focus is not on the incident itself so much as the willful self-restraint that Serena exhibited during the many earlier bad calls, both in that match and previous ones. Playing professional tennis as a black woman is used as an example of being thrown against a sharp white background, and Rankine conveys the tension inherent in trying to bury any anger that could be read as stereotypically black.

An even more egregious example of racism can be seen in the case of Zidane, who infamously head-butted Italian opponent Marco Materazzi during the 2006 World Cup. Rankine juxtaposes photographs from that game in a camera reel format against related text from several sources. The account of lip readers interpreting footage of the match reads “Big Algerian shit, dirty terrorist, nigger,” and this text is mixed in with quotes from James Baldwin, Frantz Fanon, and others on the theme of hesitation and self-restraint in the face of racist oppression. These pages place Zidane’s violent act not just in a historical context, but in the context of a world in which, as Fanon says, a person of color confronted with bigotry “must grit his teeth, walk away a few steps, elude the passerby who draws attention to him,” and suppress his justified rage for the sake of avoiding a disturbance.

If black anger is something that must be suppressed in professional sports, the reverse is true in art. Referencing the artist and comedian Hennesey Youngman’s brilliant YouTube series Art Thoughtz, Rankine suggests that a depersonalized black rage can be commodified in the art world, but that this disassociated version of human emotion is quite different from the real thing as experienced privately by an individual.

The book is devoted to capturing that latter, more human, feeling. The aim is to make the small frustrations and humiliations feel real and sharp rather than abstract and dull. Reading it is not a rousing experience; unlike Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, it cannot be described as the bible of a social movement. It is too personal, too prickly. There is something profoundly uncomfortable about reading Citizen, and the repeated phrases seem to close in on you to claustrophobic effect. This is by design; the effect is not shock or outrage but a dull sense of dread, as if the next dehumanizing slight were just around the corner.

Citizen is unique in that is plays on a particular kind of empathy – not simply white empathy, but the empathy of the academic and the intellectual; in short, the empathy of the kind of person who would purchase a book of contemporary experimental poetry. Rankine knows her audience, and she knows that they will be able to recognize the distinctly bourgeois environments she describes (and in which she resides). This identification allows for a different kind of response than, say, a professor reading about stop-and-frisk or an MFA student seeing a photo of a burning cop car on the front page of a newspaper. By situating herself firmly among the black bourgeoisie, Rankine is able to show the sly manner in which racism crosses lines of class and professional stature. None of the signifiers of middle-class life – not a tennis lesson, not a Caesar salad, not a successful academic career – can fully guard one against the drawbacks of being black in America.

There is no overarching moral to Citizen, no set of instructions on how to heal the sutured racial wound that keeps coming apart at the seams. There is merely the opportunity to put oneself in another person’s shoes, an opportunity Rankine refuses to muddle with overly abstract language. This is what happened, she tells us again and again; this is what it felt like.

Copyright 2015 Rob Bryan