Black Artists and the March Into the Museum

After decades of spotty acquisitions and token

exhibitions, American museums are rewriting the

history of 20th-century art to include black artists.

The painter Norman Lewis rarely complained in public about the singular struggles of being a black artist in America. But in 1979, dying of cancer, he made a prediction to his family. “He said to us, ‘I think it’s going to take about 30 years, maybe 40, before people stop caring whether I’m black and just pay attention to the work,’ ” Lewis’s daughter, Tarin Fuller, recalled recently.

Lewis was just about right. In the last few years alone, his work has been acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. This month the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts opened the first extensive survey of Lewis, an important but overlooked figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement — and a man who might well have been predicting history’s arc for several generations of African-American artists in overcoming institutional neglect.

An untitled oil on canvas, from 1949, by Norman Lewis.Credit Estate of Norman W. Lewis, Courtesy of Iandor Fine Arts, New Jersey. After decades of spotty acquisitions, undernourished scholarship and token exhibitions, American museums are rewriting the history of 20th-century art to include black artists in a more visible and meaningful way than ever before, playing historical catch-up at full tilt, followed by collectors who are rushing to find the most significant works before they are out of reach.

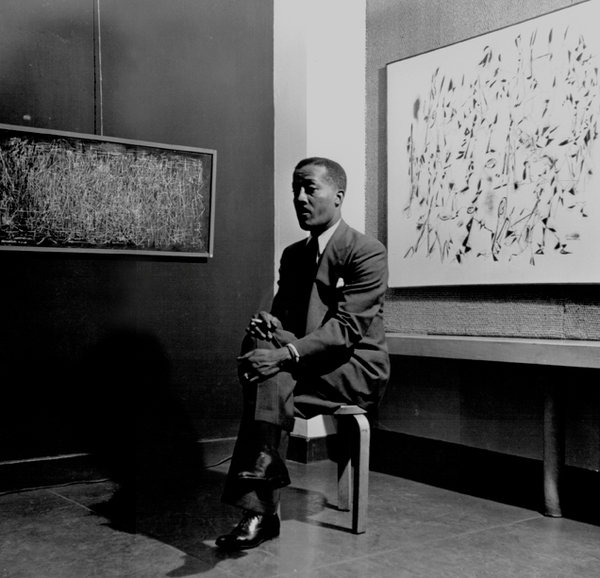

An undated portrait of the artist Norman Lewis, who died in 1979. Credit Willard Gallery Archives “There was a joke for a long time that if you went into a museum, you’d think America had only two black artists — Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden — and even then, you wouldn’t see very much,” said Lowery Stokes Sims, the first African-American curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and later the president of the Studio Museum in Harlem. “I think there is a sea change finally happening. It’s not happening everywhere, and there’s still a long way to go, but there’s momentum.”

The reasons go beyond the ebbing of overt racism. The shift is part of a broader revolution underway in museums and academia to move the canon past a narrow, Eurocentric, predominantly male version of Modernism, bringing in work from around the world and more work by women. But the change is also a result of sustained efforts over decades by black curators, artist-activists, colleges and collectors, who saw periods during the 1970s and the 1990s when heightened awareness of art by African-Americans failed to gain widespread traction.

In 2000, when Elliot Bostwick Davis arrived at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as chairwoman of its Art of the Americas department, there were only three oil paintings by African-American artists in the wing, she said, and not many more paintings by African-Americans in the rest of the museum’s collection. “I had to deal with a lot of blank faces on the collections committee, because they just didn’t know these artists or this work,” said Ms. Davis, whose museum has transformed its holdings in the last several years.

Over just the last year, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo., have hosted solo exhibitions devoted to underrecognized black artists. Within the last two years, the Metropolitan Museum has acquired a major collection of work by black Southern artists, and the Museum of Modern Art has hired a curator whose mission is to help fill the wide gaps in its African-American holdings and exhibitions.

A More Even Playing Field

In interviews with more than two dozen artists, curators, historians, collectors and dealers, a picture emerges of a contemporary art world where the playing field is becoming much more even for young black artists, who are increasingly gaining museum presence and market clout. But artists who began working just a generation ago — and ones in a long line stretching back to the late 19th century — are only now receiving the kind of recognition many felt they deserved.

Like Norman Lewis, most of these artists showing up for the first time in permanent-collection galleries — including the painters Beauford Delaney, Alma Thomas, Bob Thompson, Aaron Douglas and William H. Johnson — did not live to see the change. But others, like the Los Angeles assemblage sculptor Betye Saar, 89, and the Washington-based abstract painter Sam Gilliam, 81, are witnessing it firsthand. The Chicago painter and printmaker Eldzier Cortor, who worked in New York for many years and died at 99 on Thanksgiving Day, lived to see his work featured in the inaugural show of the new downtown Whitney Museum. Mr. Cortor had been fielding curators’ inquiries with increasing frequency and donating pieces he still owned because the market had ignored them for much of his life.

“It’s a little late now, I’d say,” he observed dryly during an interview last month in his Lower East Side studio. “But better than never.”

Eldzier Cortor's 1982 work “Still Life: Souvenir No. IV.” Credit Eldzier Cortor, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Betye Saar’s “Dat Ol’ Black Magic” (1981). Credit Corcoran Collection, The Evans-Tibbs Collection, National Gallery of Art And while it was bad enough for male artists, black women faced even steeper obstacles. “We were invisible to museums and the gallery scene,” Ms. Saar said.

Through the rise of Modernist formalism and, especially, as abstraction took hold, black artists were often at a disadvantage because their work was perceived by the white establishment as formally “lesser” — too often figurative and too narrowly expressive of the black experience.

But even abstract artists like Lewis, who resisted pressure from within the black art world to be more overtly political, were eclipsed — in part, paradoxically, because when curators did seek out black artists’ work, figuration helped them check off a box. “Up until about five years ago, when curators came to us, they were really only interested in narrative works that showed the black experience so they could demonstrate in no uncertain terms to their visitors that they were committed to representing black America,” said the New York dealer Michael Rosenfeld, who has shown work from black artists and their estates for decades. One indication that serious change is afoot, he said, is that more and more museums are seeking prime abstract works by black artists.

Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, said that even within MoMA’s strict vision of Modernism, there were black artists — like the abstractionist Alma Thomas — “who would have absolutely, comfortably fit into the narrative.” But the museum bought its first Thomas works only this year.

“It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work — with some truly wonderful exceptions, but exceptions that prove the rule,” she said, adding that the way the museum was making up for lost time was by actively buying works, “putting our money where our mouth is.”

Lowery Stokes Sims, the first African-American curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and later the president of the Studio Museum in Harlem. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times Museums Make Up Ground

A handful of institutions — among them the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Newark Museum and the Corcoran Gallery of Art (now closed) — have been regarded as ahead of the curve. As others make up ground with gathering speed, said Edmund Barry Gaither, director of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Boston, “I think what we’re seeing now is the aggregation of forces that have been in motion for at least the last half-century.”

He points to black collectors and historically black colleges, like Howard University and Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), which were buying work when few others were. Another force was the founding of the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1968 and pioneering exhibitions that began to change the conversation, like one Mr. Gaither organized at the Museum of Fine Arts in 1970, “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston”; and “Two Centuries of Black American Art,” curated by the scholar David C. Driskell in 1976 for the Los Angeles County Museum.

The shows pushed “curators and historians to admit there was a whole body of art out there they hadn’t known,” Mr. Gaither said. “They showed how a discussion about African-American art is inseparable from a discussion of American art. One can’t exist without the other.” And slowly — far too slowly, he added — the seeds that were sown changed academia and curators, of all races, who are now in charge of permanent collections and exhibitions.

Gavin Delahunty, a Dallas Museum of Art curator who recently organized a show devoted to Frank Bowling, a Guyanese-born abstract painter who has long worked in New York, said a growing number of curators emerging from graduate programs since the late 1990s felt “like we were educated to address an imbalance in representation.”

Museums are expanding their collections of 20th-century artworks by overlooked African-Americans. What artists do you think they should include and why?

“And it’s very natural to me that it’s what we should be doing now in our positions,” he said, adding, “I think there’s a real sense that the doors are pretty wide-open now.”

Mr. Axelrod, who donated and sold most of his American collection to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2011, added: “As we became exposed to it, more collectors came to the same conclusion: There are great pieces out there. These are great artists. Why haven’t I seen them before? And I’d better get them now before they’re all gone.”

A basketball hoop as light fixture by David Hammons sold for $8 million in 2013, putting him among the most expensive living artists. Credit David Hammons, via Phillips

While the market is catching on, it is doing so slowly and unevenly. Auction prices for the most sought-after contemporary black artists are very strong now when compared with their peers. A David Hammons basketball hoop as chandelier sold for $8 million in 2013, putting him among the most expensive living artists. Paintings by Glenn Ligon and Mark Bradford have recently sold for more than $3 million, and Kara Walker, whose pieces exploring the horror of slavery are tough sells for collectors’ homes, has approached the half-million-dollar mark. But prices for critically successful artists who came of age earlier, even as recently as the 1960s and ’70s, still lag behind what many dealers think they should be. Mr. Gilliam, who represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1972 and whose draped canvases have had a strong influence on younger painters trying to rethink the medium, has only recently broken $300,000 at auction, though works by Mr. Gilliam on view recently at the Frieze Masters art fair in London were priced at up to $500,000.

“I’m sorry, but I really believe that if he were a white artist, you wouldn’t be able to afford him now; you wouldn’t be able to touch him unless you had several million,” said Darrell Walker, the former professional basketball player and coach, who has collected works by Mr. Gilliam, Norman Lewis and other black artists for more than 30 years.

Sam Gilliam’s “Empty” (1972). Credit via Christie's

A Rush for the Best Works

Sam Gilliam’s “Empty” (1972). Credit via Christie's

A Rush for the Best Works

As the gauge begins to move toward correction, more collectors and museums are scrambling to find the best works. “The prices are now well beyond what I could do without major financial sacrifices to buy just a single painting,” said James Sellman, who, along with his wife, Barbara, has been collecting work by self-taught black artists like Thornton Dial for decades.

Mr. Sellman is on the board of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta, which last year donated a major collection of 57 pieces by African-American artists from the South to the Metropolitan Museum, a gift Thomas P. Campbell, the Met’s director, called “a landmark moment” in the museum’s evolution. (It came 45 years after a widely derided Met exhibition, “Harlem on My Mind,” which was intended to celebrate the cultural history of black Americans but contained no work by painters and sculptors with flourishing careers in Harlem.)

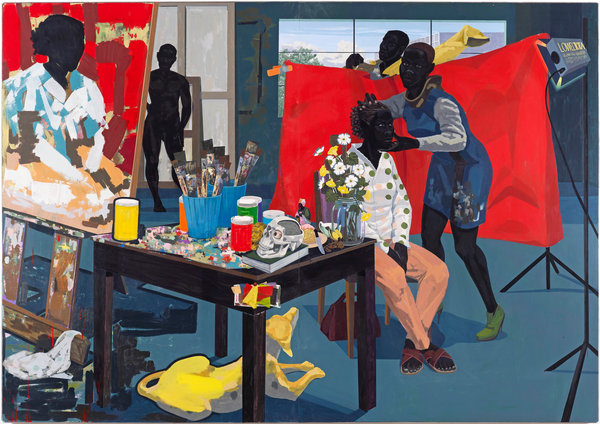

Kerry James Marshall’s “Untitled (Studio)" (2014). Credit 2015 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Kerry James Marshall

A show organized around the Souls Grown Deep donation is being planned by the Met, and next fall, at its new Met Breuer building, the museum will host a retrospective of the work of the highly sought-after contemporary painter Kerry James Marshall, making for perhaps the most concentrated focus on work by African-Americans in the museum’s history.

But Ms. Sims has been around long enough to know that the art world does not always move in a consistent direction, and warned that such progress in many ways remains fragile. “The canon is like a rubber band,” she said. “You can stretch it, but there’s always the danger it’s going to snap back.”

Thelma Golden, the current director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, said, “Yes, things are better.” But, she added: “What we need to continue to understand is that the exhibition and collection of this work is not a special initiative, or a fad, but a fundamental part of museums’ missions — and that progress is not simply about numbers, but understanding this work, in the context of art history and museum practice, as essential.”

Link to full article with videos