At the Met: Irving Penn and Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons

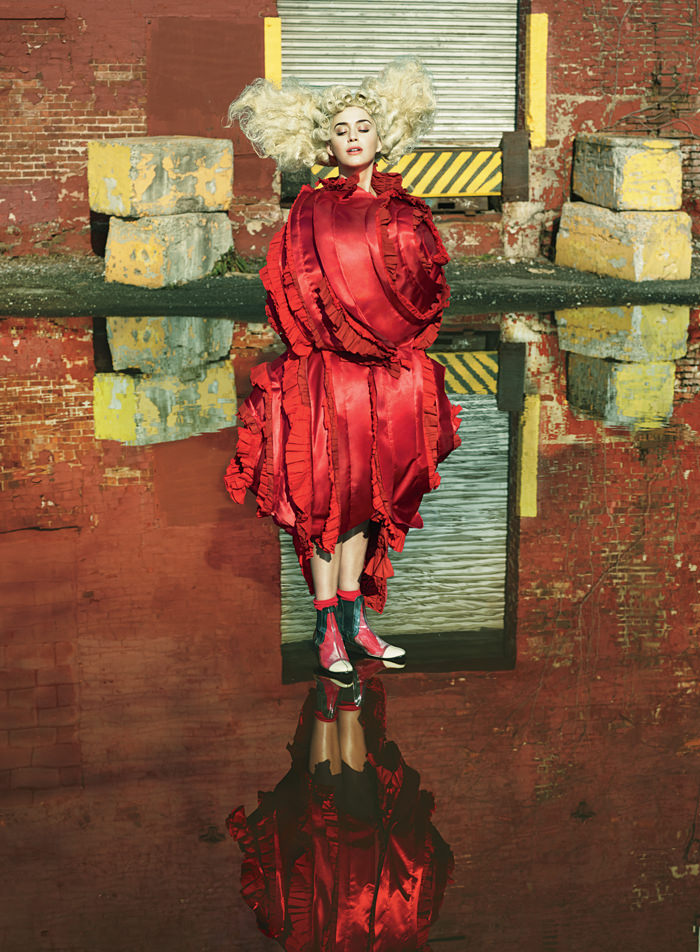

Katy Perry in Comme des Garçons, Vogue Magazine

One of New York City’s most beloved treasures that never goes out of style is the Metropolitan Museum of Art; anyone who inhabits one of the five boroughs of the city is just a train or bus ride away from complete and utter artistic splendor. One can behold works of the Masters—from Picasso and Renoir to Irving Penn and Rei Kawakubo—for as little as a penny. Currently on view are exhibits featuring the work of Irving Penn and Rei Kawakubo for fashion house, Comme des Garçons. I went to view both spectacles in the same day and saw Irving Penn’s photographs first. This retrospective of Penn’s work is the largest to date and celebrates the centennial of the artist’s birth.

I was greeted with one of my favorite of his photographs: his 1947 still life entitled “Theatre Accident.” The print depicts a woman’s purse spilled open and its revealed contents: a single clip-on pearl earring, various pills and capsules, a key, a bobby pin, a broken cigarette, opera glasses, and a pocket watch. We also see the woman’s patent leather shoe as she stands by the gold purse, the “accident.” One of the reasons I love this photograph so much is because, to me, it feels like we, the viewers, are being let in on a little secret. What a lady keeps in her handbag is private and these items are clues to some of her innermost thoughts and desires. These objects represent facets of her life and personality. These are things that all lead to the number one question we want to ask that mysterious woman at the theatre: “Who are you?” Rattling off these items shown in the photograph reminds me of Joan Didion’s packing list in The White Album. Two American artists—Didion and Penn—used an array of everyday items and made them into something special and unique. After all, art is all about context.

Theatre Accident, New York (1947)

The rest of the Penn exhibition was astounding: a different room for nearly every period. At first we were greeted with still lifes and objects, including a beautiful watermelon that resembled a wicked, pink-gummed grin, a torn baguette, a lone cherry and a housefly romancing a lemon (Still Life with Watermelon, New York). The exhibition included early work from the 1930’s all the way until the 2000’s. The theme ranged from signs seen on the Bowery to discarded cigarette butts and infamous portraits of some of the world’s greatest artists and celebrities to the everyday man (butchers, fishmongers, bakers, etc.), fashion models, nudes and Cuzco natives.

I have to say that some of my favorite Penn photographs are the portraits. I get such an overwhelming feeling of enjoyment upon seeing how a camera captured some of my favorite writers such as Truman Capote, Carson McCullers and T.S. Eliot. I also love seeing how Penn chose to “see” Audrey Hepburn through his lens and the way he caught Salvador Dali in an iconic pose that sort of epitomizes how we think of the man who spoke of himself in the third person and helped to define Surrealism. It’s fascinating to see how Penn photographed people who were so accustomed to having their photo taken but it’s almost even more incredible how he photographed those who were never the subject of a photograph. His work with the people of Cuzco is extraordinary because it is completely natural; these people had probably never been the subject of a photoshoot before and, in traditional clothing, they owned the spotlight and looked at the camera without any pretension. Without any artifice, Penn’s photographs of parents with their children captured something very special and rare.

Truman Capote, New York (1948)

Irving Penn was such an astounding artist because he was so versatile and could photograph anything or anyone: his Vogue covers are among some of the most beautiful in print. He could photograph “The Twelve Most Photographed Models” and then a man peddling fruit and the works would have the same amount of beauty and intensity. These photographs turned out quite differently from one another but the craft with which the subjects were captured is the same. This is why, in my humble opinion, Penn had a career spanning seventy years. Whether he was photographing his wife, Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in a Balenciaga dress the color of cocoa, Dovima in a Spanish hat, Dorian Leigh in Dior or abstract nudes, the beauty was always intense but never heavy-handed or overdone. Each subject appears effortlessly elegant.

Penn’s nudes are abstract in the way that he avoided capturing an entire body. Most of his nude photographs only reveal a body from the neck downward or simply a naked torso and thighs. A lot of the women in the photographs are contorted in ways that make the photographs interesting: their breasts assume soft, unexpected shapes while the nipples don’t always point outward towards the camera. Penn photographed women in a real way: he revealed the curves of a woman’s belly, the natural drooping of her breasts, the imperfect tufts and tangles of pubic hair. These qualities in the work all gather together to make it an extraordinary body of almost endless images and details.

The costume exhibit that is currently on view at the Met (through September 4th) is the work of fashion designer Rei Kawabubo for Comme des Garçons. It is entitled: “Art of the In-Between” and, upon seeing the pieces, I can see why. Kawakubo has always been a designer to push boundaries and has tried to find a space for her work “in between” categories, so to speak. The breadth of the work doesn’t seem like it fits into any category except for the one it’s defined for itself. The differences between high and low fashion as well as traditional and abstract beauty are all on display in this exhibition. One of the things that I was most struck by was the use of color (this probably sounds odd because shape is the predominant element that most notice straight away).

The color of the garments (which are more like sculptures that can be worn) was so striking because of the lighting: it was so bright, almost sterile. I felt like I had seen the future and was about to enter a fabulous capsule that would catapult me into outer space. The red of the tulle and the tartans in contrast with the stark white backgrounds was very intense: like blood on freshly fallen snow. Shiny patent leather, puffed sleeves, crooked bustles and bodices with unfinished trim and asymmetrical hems all combine in this show to create a dazzling effect. The show is actually divided into nine “aesthetic expressions” that include: Absence/Presence, Design/Not Design, Fashion/Anti-Fashion, Model/Multiple, Then/Now, High/Low, Self/Other, Object/Subject, and Clothes/Not Clothes.

All of these categories that Kawakubo has discovered in her process help us, as a viewer, to understand more clearly the intent of the pieces. For the fashion novice, it can be helpful to realize upon viewing that international pop starlet, Katy Perry wore some of these looks in a recent issue of Vogue (above) and Lady Gaga was seen out and about in one of the oversized dresses on display. These moments in popular culture can help put some of these works of art into context. I must say that I was also very impressed by the headpieces and wigs by Julien d'Ys; they completed the looks. Even if a non-fashion lover visits this exhibition, I think they will see that it goes deeper than simply fashion and that the work is truly original. Whether or not one decides to visit the Penn retrospective or the Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons costume exhibit, it is inevitable that an interesting time will be had.