Review of Ronit and Jamil

I turn fifty this year—a distinction I share with The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the famed Summer of Love… and the Six Day War that brought victory to the state of Israel and began the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights that continues down to this day. Sgt. Pepper holds up well enough, but most fans now prefer Revolver or Rubber Soul; the Summer of Love very quickly turned to the Winter of Discontent in 1968; the Occupation sadly remains the same, a seemingly perpetual trap for both the Israeli and Palestinian peoples. For as long as I can remember—my entire lifetime—this constant, deeply complicated conflict has been a part of my consciousness.

But I’ve merely observed this decades-long tragedy from afar—for those who have lived within this limbo of sectarian violence, hatred and recrimination, the burden of this deeply-rooted division over ancient faiths and sacred land falls with a crushing, existential hand. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus declares that “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” For Israelis and Palestinians alike, wherever they stand on the Occupation, history must often feel like a fifty-year bad dream—a night terror that offers no release, only more paralysis.

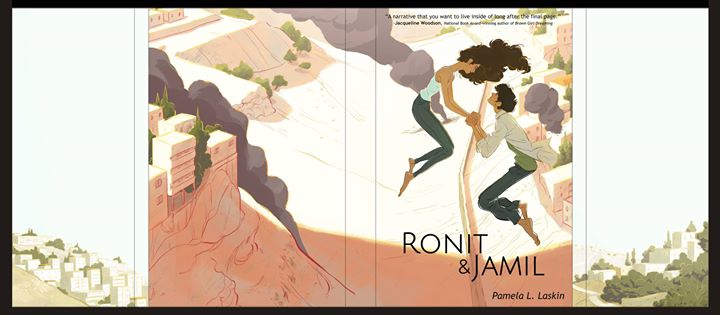

It is this history and its engulfing burden that forms the heart of Pamela L. Laskin’s verse novel, Ronit & Jamil, a book that is simultaneously one of the most moving evocations of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and one of the most intelligent and penetrating uses of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juilet in recent memory. It is History itself that raises those archetypical young lovers from merely star-crossed to the bearers of all the embedded misery in these past decades of religious and racial enmity that has been the fate of these two “peoples of the Book.”

While there have been numerous permutations of Shakespeare’s play across all media, few have taken the conflict between two house, two families, to the level of existential dread that Ronit, the daughter of an Israeli pharmacist, and Jamil, the son of a Palestinian doctor, must navigate when love instantly, mysteriously blooms between. Accompanying their fathers to the dilapidated clinic where they conduct a mutually beneficial business arrangement, the two teens catch a glimpse of one another (after both being warned by their fathers not to look at each other); that’s all it takes, in true Romeo & Juliet fashion. The lightning strikes, and there is no turning back. “Arab boy,” declares Ronit, “with your gaze/ my skin/ slips off of/ my heart.”

Laskin unfolds the story in acts, like Shakespeare, and in poetry, skillfully using free verse in short, imagistic lines & stanzas but also seamlessly incorporating received forms: pantoums, ghazals, and two devastating sonnet crowns in which the young lovers’ fathers lament this forbidden relationship. The bulk of the tale, however, is told in Ronit and Jamil’s voices; Laskin cleverly doesn’t always identify, via a poem’s title, who is speaking until the reader is deep in the poem. This has the effect of blurring Ronit and Jamil in much the same way their love is permanently blurring the boundaries between them—the reader quickly understands that, in addition to the way passion dissolves two beings into one, there is also the simple fact that Ronit and Jamil share just as much, if not more, than the wall and politics that separate them. Two teenagers, living under the same parental constraints, kicking against the mirrored beliefs of their families, but also living under the shadow of History. Even amidst their secret raptures, they must acknowledge this, as in “Ronit’s Text”: “You say land/ was taken/ from your farmers/ to build the fence,/ and olive trees/ were uprooted.// This makes me sad./ This makes me scared.” The response in “Jamil’s Text” faces it head on:

I didn’t want to make you

scared,

sad,

it’s just when we talk about

whose land it is

as the rockets fly from Gaza,

and one lands

near your home;

I want you to understand

there are no answers

except for us.

Two teenagers in love, sending text messages, declaring their love is something the world doesn’t understand—what could be more mundane? But Ronit and Jamil’s context has raised the stakes, and there is much more than the disapproval of two families to overcome. A politics of hate and oppression, of terror and desperation, hover over the lovers, causing momentary doubts and difficulties. Watching Ronit and Jamil struggle with the enormity of their love against the enormity of their land’s history gives the story a frisson that many take-offs of Romeo and Juliet can’t help but lack. Unlike Shakespeare, the tragedy in Ronit & Jamil has already happened; is happening; will keep happening. Against such a backdrop, how can their love survive? The solution is tenuously, brightly hopeful and yet deeply sorrowful.

It’s Laskin’s unerring directness and simplicity of language, shot through with images and lines that gleam without overwhelming the narrative, that makes Ronit & Jamil such a compact, emotionally powerful Young Adult novel (and, like so many fine YA works, one which can be enjoyed by anyone of any age). Perhaps history is permanently star-crossed, but history also has moments when the stars align, and even those in the shadow can find a way forward. Fifty years is a long time; fifty years, the blink of an eye. Laskin’s beautiful and fraught evocation of Romeo and Juliet shows that the way forward is, as so often, only through love, as Jamil declares in “Jamil’s Dream”:

Ronit,

I hope you get this text.

I had a dream;

it was amazing!

I heard your voice—

Hebrew and Arabic words

we have shared:

how you embrace my exit

how you are my ancestor

and we must be the same.

--30--